Rhododendron-covered berms create both color and privacy

How Evergreen Was Created: History of the Garden Since 1983

- Evergreen’s Natural Legacy

- Gardening by Subtraction: Cleaning Up, Weeding, and Pruning

- Grading: Making Paths, Ramps, and Berms

- Water: Streams, Pools, Cascades, Waterfalls, and Causeways

- Planting

- Furniture and Sculpture

![]()

- First Public Opening, 1994

- Evergreen in the Open Days Program, 2010-2017

- The Fire of 2015

- Evergreen Foundation Formed, 2016

Evergreen was the result of a wonderful coincidence, which is recounted below by Robert Gillmore, the landscape designer who created the garden.

Many people think I purchased Evergreen—or, rather, the property that became Evergreen—because I recognized it as an amazing site that could be transformed into an amazing woodland garden. The thought is totally reasonable—and completely wrong.

In fact, when I bought Evergreen in 1983, I actually knew almost nothing and cared even less about ornamental gardening or landscape design. I bought the property not because I loved the land but because I loved the house. It was a beautiful Colonial Cape built in the style of Royal Barry Wills, the 20th-century Boston-area architect renowned for his picturesque interpretations of Cape Cod houses—graceful, usually white clapboard or shingled structures distinguished especially by their large, generous multi-paned windows.

Built in 1941 by Dr. Richard Backus, the house had four (!) fireplaces and handsome crown molding, paneling, and other fine details both inside and out. There was ample space in the basement for a large office (I used to be a legal publisher), and the wing of the house where Dr. Backus once maintained his medical clinic had been transformed into a small apartment that provided rental income.

![]()

My interest in landscape design began only after I bought the property. There were two patches of grass next to the house, and, of course, I had to mow them regularly. And even though the mowing didn’t take much time, it vexed me. Surely, I thought, I can do something less …destructive in this space than simply hack away at plants all summer long, year after year.

Why, I wondered, could I not grow something that didn’t need to be amputated every week, something whose growth would actually be welcomed; maybe something that would be more interesting and more colorful than grass. (See What to do About Your Lawn.)

I took these questions to a nursery, where a helpful woman introduced me to junipers, hostas, red Japanese barberries, and purple-leaf sand cherries—none of which, of course, I had ever heard of. How fast would they spread? I asked. By that I meant, How fast could they replace my grass?

I brought home about two dozen plants, including about eight hostas with variegated green-and-white leaves and eight more with plain green foliage and inserted them into the thin patch of grass on the street side of the house.

I didn’t know how the hostas should be arranged, so I planted them in probably the worst possible way: a checkerboard pattern, in which every variegated hosta simply alternated with a plain green one. I spent the next several weeks trying to figure out why the arrangement didn’t look right.

My first attempt at landscaping, however, was much more than a failed planting scheme. It was the genesis of an additional career—actually a calling that gave me as much pleasure as anything I had done before or since. As I listened to my bliss (Joseph Campbell’s words) I discovered that I harbored a deep passion for designing and making naturalistic landscapes. After a voracious amount of reading and lots of looking at and thinking about landscapes, I not only learned why plants (like my first hostas) should usually be planted in drifts or sweeps of only one variety (not two or more). I was also delighted to discover dozens of other ideas and insights that led to the creation of Evergreen and to many other naturalistic landscapes for my clients. (See Robert Gillmore’s Residential Landscapes.)

About the same time that I started replanting my front lawn, I began looking closely at my woods, and I started seeing them the way Michelangelo looked at marble. He saw not only the block of fine white stone but also the statue that (as he famously said) already existed in the marble and needed only to be revealed by cutting the stone away from it. In the same way I saw my rough woods as the precious raw material from which a beautiful woodland garden could be created.

![]()

Evergreen’s Natural Legacy

The raw material—the marble, as it were—of Evergreen was and is extraordinary. As I was discovering my passion for naturalistic landscaping, I also discovered—several years after I bought my property—that, purely by happenstance, I owned a magnificent natural legacy, a landscape that just begged to be transformed into what I saw as an extraordinary woodland garden.

For one thing, I noted, there were the magnificent trees: a forest of large, handsome white pines that covered the entire property. (And much of my neighbors’ property, too.) The older trees had developed picturesque deep-furrowed black-brown bark, and the largest specimens were as much as three feet thick at the base, with wide, flaring roots, some of them four or five feet across as they entered the earth. Like other giant trees, they were some of nature’s most impressive natural sculpture.

At least twice a year, the huge trees rain down a flurry of dead needles—so many that they create thick, warm brown carpets on the forest floor.

There are few forests quite so beautiful—so striking, yet also so spacious and serene—as a mature pine woods. And I was delighted—actually ecstatic—to discover that I owned one.

There were also the rocks: dozens of gray granite “glacial erratics,” so called because they were strewn across the land by a vast glacier in the last Ice Age. Most of the rocks are substantial, some as large as a Volkswagen Beetle, at least a couple as big as small cabins. Virtually every one of them was a handsome piece of natural stone sculpture that rested on the earth at its widest dimension and narrowed like a bare mini-alpine peak as it rose to its highest point.

Then there was the exciting shape of the land itself. Many residential lots are as flat as airports. Evergreen is an irregular hillside that slopes both from north to south and west to east in a series of alternating inclines and terraces. It drops a total of 50 feet from its highest point, in its northwestern corner, to its lowest point, on a seasonal brook near its southeastern edge.

The brook itself was lined with dozens of moss-coated rocks, both large and small. Because the streambed sloped steeply from north to south, the brook created countless cascades as it rushed downhill. Downstream from the cascades was a shallow pool walled with brooding moss-covered boulders.

Rising steeply up from the East Bank of the brook were gray granite cliffs, some almost vertical, some nearly 20 feet high.

Another prized rock feature was a cluster of huge glacial erratics that looked like the opening of a cave.

Besides the massive pines, there were other flora, including:

- Smaller oak, maple, sassafras, and witch hazel trees;

- A few low-bush blueberries;

- Large clusters of hay-scented ferns, one of which was the size of a very large room;

- Bright green carpets of Canadian mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), a spring ephemeral also known as false lily-of-the-valley;

- A few patches of partridgeberry (Mitchella repens) and winterberry (Gaultheria procumbens), both handsome evergreen ground covers;

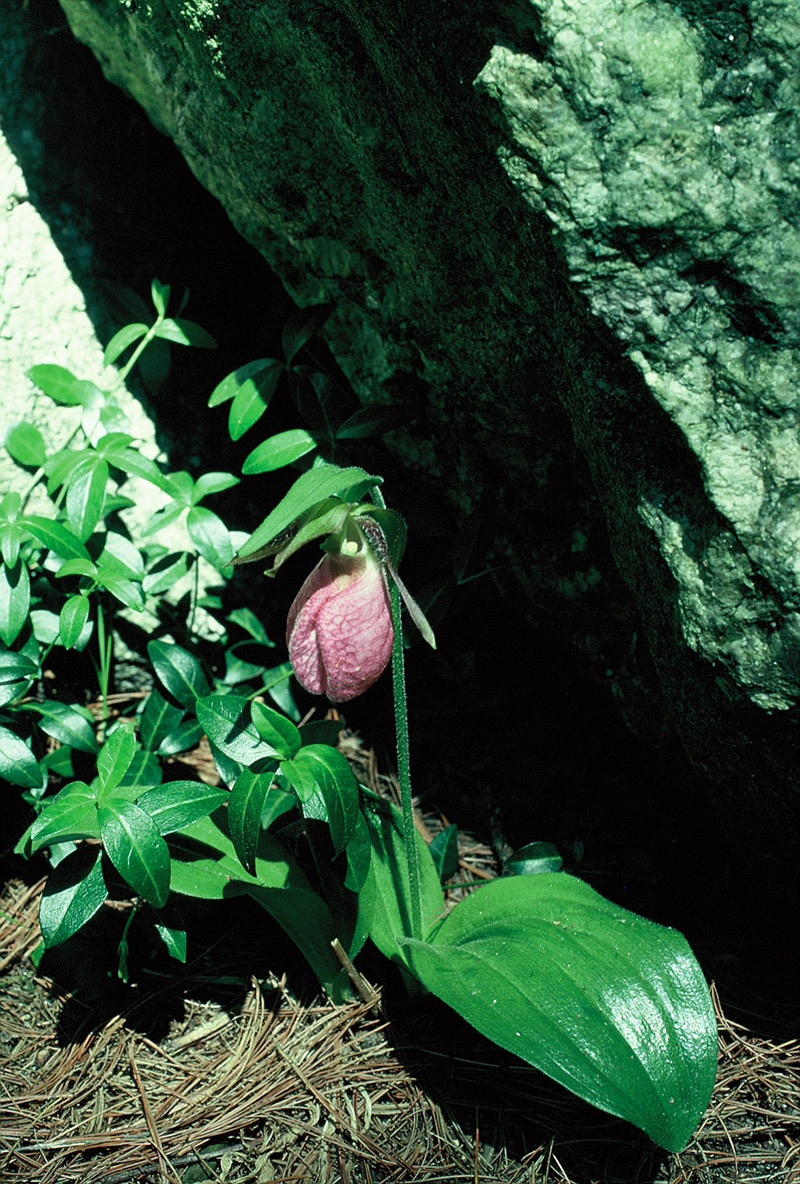

- Herbaceous wildflowers, including pink lady’s-slipper orchids (Cypripedium acaule); Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), named for the leafy hood that hangs over its seed cluster like the canopy of an old-fashioned pulpit; Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum commutatum), distinguished by its graceful leaning fronds, by long leaves growing perpendicular to their stalks, and by a row of tiny, white, bell-shaped flowers hanging from the plant;

- European, or common, barberry bushes (Berberis vulgaris), whose leaves and berries turn red in the fall, growing robustly along the stream.

![]()

Altogether, the natural legacy of Evergreen was literally priceless. Many of its smaller trees and wildflowers could have been bought at a nursery; but its big trees and, of course, its rocks, cliffs, and stream—the most impressive parts of the legacy—were not available anywhere at any price. Because they were already here, already in place, the largest and most elaborate features of Evergreen—its trees, rock, and water—did not need to be bought or installed. They came with the property when I bought it. Much of Evergreen, in other words, already existed. All I had to do was complete it.

The pines, the rocks, and the shape of the land became what gardeners call “the bones” of the garden. They helped determine where the paths, plantings, and several outdoor “rooms” would go. The larger rocks, in fact, helped form some of the rooms. The pines, the cliffs, the cavelike boulder cluster, the brook, the pool, and most of the other rocks scattered about the site remain some of the garden’s most impressive focal points.

![]()

Gardening by Subtraction: Cleaning Up, Weeding, and Pruning

My woods boasted not only handsome ornamental assets like boulders and large trees. Like most woodlands, they also included small, scrawny trees, dead branches, brush, and other, less ornamental features that only cluttered up the landscape. Like Michelangelo’s block of marble, they obscured the beauty hidden behind them. Like the unwanted marble, they had to be removed. I call this process gardening by subtraction.

Most gardening involves adding things—plants, sculpture, furniture, etc.—to the landscape. In gardening by subtraction, you take things away. Like Caesar’s Gaul, I divide the process into three parts: cleaning up, weeding, and pruning.

- Cleaning up is removing all dead wood, both standing and fallen, large and small, as well as all litter and other debris from the site.

- Weeding is removing any live trees, shrubs, and other plants that detract from the beauty of the site.

- Pruning is removing unwanted parts (mainly branches) of trees, shrubs or other plants.

Gardening by subtraction at Evergreen was a relatively easy job for several reasons:

- Many of the rocks and trees—and all of the larger ones—didn’t need to be removed. On the contrary, they were prized possessions, among the most important natural assets of the site.

- Many diminutive but well-shaped deciduous trees were also left alone because I valued their warm yellow fall foliage and their ability to help screen neighboring houses when they leafed out.

- Showy herbaceous perennials such as lady’s-slipper orchards, Jack-in-the-pulpit, and Solomon’s seal were also untouched, because they’re striking accents.

- Because Evergreen gets little sunlight, most of the undesirable understory plants such as brushy shrubs and small deciduous trees were starved for light. As a result, they were few and often small, so they could be easily removed.

(One of the most beneficent characteristics of gardening by subtraction is that the least desirable plants are also the easiest to get rid of, and, conversely, the hardest plants to remove (mainly big trees) are, conveniently, the very plants you don’t want to remove.)

- All the plant debris was easily disposed of in berms, many of which, fortuitously, were built not far from where the debris was either found or cut.

What exactly had to be removed?

For one thing, rocks. For every handsome boulder on the site, there were at least two small stones (smaller than basketballs) that, mainly because of their size, were only litter. Conveniently, these too were easily buried in berms.

Also eliminated were many little hardwood trees such as witch hazels (Hamamelis virginiana)—small gangly species that add little to the beauty of the landscape. Their many spindly stems grow diagonally, not vertically, spoiling the striking verticality of the pines’ massive straight trunks and virtually all of the other trees in the garden. (But see Pruning, below.)

I also removed small white pines and scrubby deciduous trees such as cherry and ash. Many were skinny and obviously yearning for light under the canopy of the pines. Like the witch hazels, they contributed only clutter to the site.

Growing in and along the brook were many honeysuckle bushes (Lonicera)—homely woody deciduous shrubs, also hungry for light, that hid the brook and made it nearly inaccessible. Other unwelcome plants were a few wild raspberries and some thick patches of poison ivy farther upstream.

Among the unwanted plants were several dozen dead trees—some standing, many fallen—as well as many dead branches littering the ground.

The largest collection of dead wood was created by the former owner of the house atop the cliffs on the eastern edge of the garden. He had felled several large white pines on his property and had thrown what seemed like two truckloads of logs and branches over the bluffs. The brush covered up the lower part of the crags and, like the honeysuckles, they hid much of the brook. We conveniently buried all this debris in a berm built nearby, which screens other houses on Route 13, not far from the southeast corner of the garden. (This project is described below under Berms, or Making Your Own Ridges.)

Many of the standing dead trees were also pines. They have shallow roots, so I could get rid of the smaller ones simply by pushing them over, roots and all (sometimes after a little rocking). This job was made easier by Evergreen’s rather loose, stony soil.

Because most of the standing dead hardwood trees were small (actually, they were dead because they were small—too small to get enough light), they too could be yanked out, roots and all, just like the pines.

Only a few trees—living or dead—had to be cut down with a pruning saw. (None were big enough to require a chain saw.) As noted above, one of the nice things about gardening by subtraction is that very few large trees need to be removed. Au contraire, the larger the tree, the more desirable it (usually) is, and, therefore, the less likely it needs to be excised.

The honeysuckles in the streambed all had large crowns; but, mainly because they were growing in wet spots, they also had small, weak roots, so they came up effortlessly. And when they did—voila!—there was the brook beneath, burbling beautifully over its rocky bed.

The long vines of poison ivy came up easily, too. The trick is to pull up every one you see and to keep pulling them up every time they reappear. Eventually they’ll disappear.

I also had to deal with an impressive, 20-foot-square drift of hay-scented fern, the largest fern bed in the garden. Like the pines and the rocks, it was another generous gift of nature. Unfortunately, its unnatural-looking square shape was appropriate for a formal garden, not for Evergreen.

For a while I didn’t know what to do about it. I didn’t want to try transplanting the ferns because it’s almost impossible to dig them out of rooty woodland soil without harming them. But I also didn’t want to leave them in place.

Then an idea struck. It was another version of gardening by subtraction: I cut a gently curving S-shaped path from the northwest corner to the southeast corner of the patch. Now, instead of a big, formal, square bed of ferns, I have two graceful, irregularly curving clusters. Or, put another way, I have a delightful 18-foot pathway fringed on both sides by luscious, three-foot-tall ferns.

![]()

Finally, there was a children’s playhouse close to the north side of the house. The building was attractive enough—a tiny, brown-stained wooden cabin with a window, window box, and Dutch door—but it was too much of a focal point. It diverted attention away from the trees and shrubs and made the garden look too—for lack of a better word—”developed.” My carpenter, Tom Clatanoff, removed the house for free; he reassembled it in his own yard as a playhouse for his young son and daughter.

![]()

Pruning

Besides cleaning up and weeding, I also pruned. To open up views of the cliffs above the brook, I cut off the lower branches of trees on both the East and West Banks of the stream. But I carefully left the top branches alone so they would continue to screen the houses on top of the cliffs.

Some of these trees have little ornamental value, but I don’t mind letting them grow. On the contrary, I hope they thrive and unfurl larger and larger masses of foliage each year. I need them all—and actually a few more—to hide the development behind them.

This work was an example of selective pruning to control the view; that is, pruning both to open up a desirable vista and to block an unwelcome one.

More selective pruning occurred when I trimmed a couple of witch hazels on my neighbor’s property (with his permission). I removed just enough limbs so I could see some huge, handsome rocks in his woods. But I also took care not to cut other branches that hid another house farther away.

One witch hazel, near the northwest corner of the garden, was pruned to give it a simple, gracefully arching shape (described in the Detailed Garden Description).

The trees that required (and continue to require) the most pruning at Evergreen are its large pines. As these giants grow, they raise their needle canopies ever higher, and older branches below them receive less and less sunlight. Gradually the needles on these lower, shaded limbs die, and, finally, so do the branches themselves. As the trees grow, their trunks bristle with skinny, often-broken bare limbs sticking almost straight out from the tree, not unlike the sparse stubbly hairs of wild pigs. Unlike the long, curving, gently narrowing branches that rise gracefully away from the trunks of hardwood trees, dead pine limbs look like hideous mistakes, shockingly defacing the dark, furrowed trunks, which are as handsome as the dead branches are ugly.

With the aid of a ladder, I cut off every dead limb I could reach. The higher branches—some of them 40 feet above the ground—were removed by a tree surgeon, who climbed the trees with the aid of ropes, belts, and cleats on his boots. Like other plant debris, the dead limbs were buried in berms.

![]()

When the cleaning up, weeding, and pruning were done, Evergreen looked so much better than when I first saw it. And I hadn’t added a single plant! As a result of only gardening by subtraction, I had created a clean, open, parklike woodland dominated by massive white pines and huge handsome granite boulders. If I had stopped right there, I would already have made an elegant, idealized woodland. But the next steps made Evergreen even better.

![]()

Grading: Making Paths, Ramps, and Berms

Not surprisingly, much, if not most, garden-making is about plants. Grading is different. It’s about dirt, or, more precisely, using fill and loam to make paths, ramps, and artificial ridges known as berms.

Berms preserve the visual integrity of a garden by screening it from houses and other development. Ramps take you smoothly up and down steep grades without using steps. Paths make it easy to walk around the garden and take you to its best views.

Paths

The beauty of a garden—any garden—can be enjoyed most when it can be savored effortlessly and when you can give it your full attention—when you don’t have to worry about tripping over rocks or roots, stepping in mud or water, or catching branches in your eye, and when you don’t have to trudge up or lurch down steep paths.

The ideal garden path should be as smooth and level as possible, so smooth and gentle that you barely notice it, so smooth that you can take it for granted, like a sidewalk.

The easiest, cheapest, and most natural way to create a smooth, dry, and level path is to select a path that’s smooth, dry, and relatively level to begin with—which is why the best woodland garden paths are not so much made as chosen.

Unlike, for example, a road or a sidewalk leading to a house, the ideal woodland garden paths are usually not the shortest distance between two points; they’re very often longer—sometimes much longer. That’s because a path must often circle around major features like large trees and rocks; and because, instead of running straight up or down a hill, it traverses it diagonally, sometimes with one or more switchbacks.

![]()

Longer, winding paths not only make a garden easier to negotiate. They also enhance the garden experience. For each curve in a path reveals yet another view of the landscape. Designers call this effect progressive realization: the idea that a garden is seen, or “realized,” not all at once, but gradually, or “progressively”; not in one view, but in a series of views. The longer the paths, the larger the number of views that may be revealed; and, of course, the more time it takes to walk through a garden and the more elaborate and more extensive it appears to be. Hence the designer’s paradoxical rule of thumb: the longer the path, the larger the garden.

Many visitors ask: How big is Evergreen? Many guess that it’s two, three, or even five acres. Actually, Evergreen is only about nine-tenths of an acre.

One reason Evergreen can seem much larger than it actually is, is that it has more than a quarter-mile of paths—so many that they take you to every part of the garden, offering countless different views, from a limitless number of perspectives. Evergreen seems larger than it is, not only because it takes so long to walk through it, but because—thanks to the paths—there is so much of it to see. (It also seems larger than it is because of visual borrowing, described in the Detailed Garden Description.

![]()

Happily, most of the paths I chose at Evergreen needed little work. That’s because I was able to find level, nearly level, or very gentle grades, and much of the garden floor was already smooth enough for a footway. Some stones had to be removed (and a few branches trimmed out of the way), but virtually no fill was required.

Several paths, however, did require fill.

One was along the brook. I wanted to be able to walk easily alongside the stream so I could enjoy continuous views of the falling water. I also wanted to be as close as possible to the stream so its visual impact would be as powerful as possible, and the volume of what the naturalist John Muir called the “singing” of its cascades would be as loud as it could be.

Unfortunately, much of the stream bank, on both sides of the brook, was rough and rocky. You could pick your way over it, but the walk would be unpleasant.

The solution was simple: Build a smooth dirt path over the rocks.

First, I moved a few barberry bushes out of the way by transplanting them farther away from the brook. Then my helpers and I brought a few dozen wheelbarrow loads of fill down to the stream and dumped it on top of the stones—within a couple of feet of the water, but far enough away and high enough above the brook so the material wouldn’t be washed away. I raked the fill smooth, making sure it had a slight slope to shed rainwater. Next, I tamped down the fill and placed a few large rocks where they were needed to make sure the brook wouldn’t wash over the new path. Finally, I added a thin layer of loam to make the path look as if it had been there all along.

Now you can stroll easily along the entire length of the brook, just inches from the stream, and enjoy water-filled vistas both upstream and downstream.

I also used fill to build a short loop path that descends to and runs briefly along the West Bank of the brook. My helpers and I added just enough material to cover all the unattractive small, rough, jagged stones where the path would go.

But we carefully left all the half-dozen or so largest rocks uncovered and curved the path around them. These smooth, well-shaped little boulders provide handsome stone sculpture while defining the edges of the footway.

We also added loam on each side of the path and planted it with pachysandra. This low ground cover defines the path, unifies the site, and brings the eye down to both the boulders and the stream, making them more impressive than they would be otherwise.

I also added fill to grade the path that traverses the wide, steep slope farther up the West Bank. The path itself wasn’t steep; in fact it climbs very slowly. But because it runs across the steep grade, the footway pitched downhill so much that it twisted your feet when you walked on it.

The typical solution to this problem is “cutting and filling”; that is, lowering the uphill side of the path by cutting material away from it and raising the downhill side by filling it with the excavated material.

Cutting, however, would have disturbed too many roots—and made for some hard digging. So I opted for just filling: My helpers dumped fill along the downhill side of the path, and I smoothed it out with a rake. Now the surface of the path, from the uphill side to the downhill side, is level enough to walk on comfortably; but it still slopes enough to shed rainwater easily and dry out quickly. Like all fill-made paths at Evergreen, I covered it, for cosmetic reasons, with a thin layer of loam.

![]()

Two other paths in the garden did not merely have to cross steep grades; they had to ascend them. There was no room for the trails to climb the slopes diagonally, in a single traverse—the space was too narrow. The route had to go almost directly uphill. Nevertheless, I was able to make the paths ascend with easy switchbacks, or zigzags, adding fill and loam as needed to make the footing more level. I outlined the paths (and made sure people stayed on them) by planting shrubs and ground covers on both sides of the footway.

![]()

Ramps

Sometimes a grade is too rough or steep for any path, even one with switchbacks, so you have to replace the original grade with a gentler, artificial one. In other words, you need to build a ramp.

A ramp is a very simple structure. It’s nothing more than dirt dumped on the bottom part of a steep slope to make the grade more moderate. Obviously, a ramp costs more to build (in time and material) than a path. But an earthen ramp has many advantages:

- It’s faster, cheaper, and easier to install than stairs, steps, or a concrete ramp.

- Because it’s dirt (usually some kind of fill), it costs virtually nothing to maintain—unlike, for example, wooden or even masonry steps. In fact, because it’s dirt, it virtually never wears out.

- Unlike steps or stairs, it looks natural, so it befits a naturalistic garden.

- Like a good path, a ramp takes less concentration to negotiate than stairs or steps, so it interferes less with the enjoyment of the garden.

Even though Evergreen is a hilly landscape, there are absolutely no stairs or steps on its paths. In fact, the only outdoor steps on the entire property are concrete stairs leading to the front entrance of the Garden Cottage, and concrete-and-fieldstone stairs leading to the Visitor Reception & Exhibit Area and the rear entrance of the Cottage. Every other part of the garden is accessed entirely by dirt paths—and just two ramps.

Both ramps were built where the land drops off into the woods just south of, and not far from, the Garden Cottage.

One ramp was constructed at the edge of the driveway. Fill was dumped in the driveway and bulldozed down the bluff. I raked it farther downhill to make a long, gentle slope that curves between several trees and large rocks. I coated the footway with loam, then spread several more inches of loam on either side of the path to plant shrubs and ground covers. The ramp now takes garden visitors back up to the driveway through a white-and-green allée of variegated euonymus (described in the Detailed Garden Description).

The other ramp descends into the woods behind the massive white pine at the edge of the Visitor Reception & Exhibit Area. (It, too, is described in the Detailed Garden Description.) An early owner of the property had installed a steep flight of stone-and-concrete steps, with narrow treads, where the ramp is now. The steps were tricky to negotiate even when they were new. Forty years later, when I bought the property, they were crumbling.

The steps were too far from the driveway for an excavator or other machine to reach; so I wheelbarrowed about 20 cubic yards of fill to the site, dumped it over the steps, smoothed it out with a rake, and added the customary layer of topsoil.

Unlike the hapless steps, the ramp looks natural, is easy to ascend and descend, will last indefinitely, and cost only about $200 worth of fill and loam to build.

Berms, or Making Your Own Ridges

If you can see your neighbors’ houses from your garden, it probably needs at least one berm.

A berm is a linear mound of fill (or other material) shaped like a ridge. Built along the edge of a garden, and planted with evergreen trees or shrubs, it blocks views of houses, cars, streets, and telephone poles and reduces the noise of traffic, people, dogs, radios, etc. By insulating your garden against these and other residential development, a berm helps maintain its integrity: It allows a garden’s views of trees, shrubs, rock, water and other natural things to be unadulterated by unwanted views of manmade objects.

Some of the development around Evergreen is screened by trees growing both in and around the garden. From May until October, when the deciduous trees are leafed out, the tree screen is thick enough so you barely see houses on Route 13. But that’s an exception that proves the rule—which is that Evergreen’s privacy is created mostly by berms.

When I bought the property, much of the development around it was visible in every direction, especially from late fall until spring, when the deciduous trees were bare. That’s why Evergreen needed berms along all its boundaries.

![]()

The sites of two large berms—one near Summer Street, the other along the driveway—could be reached by heavy equipment, so they could be built with a dump truck and a bulldozer.

My helpers and I began the process by piling plant debris (from cleanup and weeding) in long rows along the center of what would be the bottom of the berms. This not only got rid of garden waste; it also clearly indicated to the contractor exactly where the fill should be dumped.

The piles of debris were covered by about 30 truckloads (about 300 cubic yards) of fill. Some of the fill was an ordinary mixture of sand and clay, which, in 1989, cost $7 per cubic yard, delivered. The rest of the fill was what Scott Rossiter, then the proprietor of Bedford Sand & Gravel, called “junk.” Junk is what’s left after topsoil is screened, or filtered, to produce “screened” loam. As the loam falls through the screen, like flour through a sieve, the “junk”—logs, branches, stumps, rocks, a little dirt, and whatever else was in the original topsoil—is left on top of the screen.

Scott sold me the junk for $3 a cubic yard, delivered. (The price was essentially for delivery; the junk (no surprise) was free. It was literally less than dirt cheap.)

There’s little, if any, oxygen deep in the ground, so (perhaps counterintuitively) the junk decays slowly, if at all. That means the berm settles very little and very gradually, if at all. This settling is acceptable, because berms need to support only plants, not buildings, and because any loss of height due to settling is more than offset by growth in the trees or shrubs on top of them.

After the fill was dumped, Scott, an artist with a bulldozer, shaped it into long, narrow ridges as much as 10 feet high. Then he covered the ridges with a 9-inch layer of good-quality unscreened loam. The unscreened topsoil actually had rather little “junk” in it, so it was suitable for planting masses of shrubs and ground covers (if not for making a smooth lawn). It was also cheaper (unsurprisingly) than screened loam: In 1989 it cost only $10 a cubic yard, delivered; screened loam was $12.

When Scott was finished, I smoothed out the loam with a rake, removing any junk as I worked. When finished, the two berms combined were about 100 feet long and 4 to 11 feet high, with an average height of about 5 feet.

![]()

All the other berms at Evergreen were too far from the street or driveway to be built by trucks or bulldozers. They had to be made by hand.

As with the machine-made berms, my helpers and I first piled plant debris where the berms would be built.

Then trucks dumped fill either in the driveway or just off the street—whatever was closer to the berm site. Then my helpers shoveled it into wheelbarrows, pushed it through the woods (on paths already cleared), and dumped it on the brush.

Luckily for my helpers, most of the fill could be wheeled across level or downward-sloping ground. (As you may imagine, you would not want to wheelbarrow any of it uphill.)

I used only sand-clay fill because, while junk can be handled with big machines, it’s way too big and bulky for a shovel.

After the fill was in place, I shaped it with a shovel and rake.

Next, my helpers dumped about nine inches of unscreened topsoil on top of the fill, and I smoothed this out, too.

In all, these handmade berms were about 250 feet long, between 2 and 8 feet high, and an average of about 4 feet high. Planted with rhododendrons—which would grow as high as 8 to 10 feet—they screen out most of the development around the garden. And as the shrubs grow taller and thicker, they shroud more and more development every year.

![]()

The brush collected near the brook—including the tons of pine logs and branches dumped at the bottom of the cliffs—was used to build a berm on the southeastern edge of the garden.

The site was on the East Bank of the brook and farther from the driveway than any other place in the garden. Carrying fill and loam there in wheelbarrows would have been a long, hard job. So I decided to build the berm with lots of pine slash but only a little material.

My helpers and I began by making a tight pile of pine logs that extended from the southern end of the cliffs to the east bank of the brook. We piled branches on top of the logs, and rotting needles and leaves on top of the branches. Then I posted several notices around town requesting donations of leaves. Conveniently, this was in the autumn, and my notices yielded several hundred plastic bags of both leaves and pine needles (some of which I raked up and bagged myself). I hauled the bags down to the berm and made small, billowing hills of dead foliage. After the piles settled, my helpers added just a few wheelbarrows of loam. When we were done, we had made a 6-foot-high, 36-foot-long berm.

The combined loam and decaying leaves made a fine growing medium. I later added a half-dozen rosebay rhododendrons to the top of the berm; today they’re screening unwelcome views to the southeast.

This project was wonderfully economical. It not only produced a beautiful berm; it also did at least four other things:

- It got rid of an enormous pile of what Scott Rossiter called junk.

- It helped reveal a lovely cascading stream.

- It exposed many square yards of handsome sheer cliffs on the East Bank of the brook.

- With the junk out of the way, a drift of the wild impatiens known as jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) emerged from the rich moist earth underneath, and it created a perfect, solid carpet of foliage, unbroken by any other plant, between the brook and the cliffs. The contrast between the soft, delicate light green leaves and the massive hard gray rock was stunning: the cliffs looked as indestructible and as permanent as the jewelweed seemed fragile and ephemeral.

The brook, the cliffs, and the jewelweed were all gifts of nature. The brook and the cliffs simply had to be unwrapped, and the jewelweed needed only a place to grow. What’s more, the berm was made simply by getting rid of debris and adding a bit of loam. Not bad for just a week or so of work! Gardening by subtraction doesn’t get any better than this!

(Full disclosure: Jewelweed needs moist soil. One summer, after a dry spell, it shriveled up and died. Fragile/ephemeral indeed! It was replaced by pachysandra, which can survive a bit of drought, especially in shady locations. Unlike jewelweed, it’s evergreen, so its foliage is effective year-round.)

![]()

Water: Streams, Pools, Cascades, Waterfalls, and Causeways

Nearly every great garden has at least some water—a fountain, a pool, a pond, a stream, a waterfall—and the reason is readily apparent:

Water is arguably the most engaging element in the garden. It offers, paradoxically, both excitement and repose at the same time. On an often-static site, it provides the motion of moving water; smooth water, on the other hand, mirrors the motion of clouds. In a woodland garden, whose major colors are grays, browns and greens, a stream’s ripples and cascades offer glistening streaks of white; when its smooth surface mirrors the sky, water brings its blues, grays, and whites to the woodland floor. Water can be the strongest focal point and the most interesting accent in an entire garden. And its many sounds—from lapping, to trickling, to shushing, to splashing, to wild surging—add aural excitement to an otherwise quiet place. If you have water in your garden, you may give it more attention than anything else there.

![]()

Evergreen has no ponds or large streams, but its long cascading brook is the most dynamic feature on the eastern edge of the garden. I explained above how the brook was a gift of nature that needed to be unwrapped—mainly by taking away the honeysuckles growing in its bed—and how paths were built so one could easily walk close to the falling water.

![]()

I also wanted to build two crossings of the brook, not only to walk to (and along) the other side, but also to create long upstream views of cascades. I knew these vistas would be among the most dramatic in the garden. For instead of merely standing beside the brook and seeing a few cascades at an oblique angle, I would be able to stand at the middle of the brook, look upstream, and see cascades flowing directly toward me. No other views of the brook would be nearly so full of so much falling water.

I knew I could build or buy two arched bridges to span the brook, but I wanted to avoid the large cost of acquiring—and maintaining—two sizable wooden structures. I also preferred a less architectural, more natural solution. So I built two dirt-and-stone causeways instead of bridges.

Like the berm made out of tree debris, the causeways were models of economy. They were built almost entirely with 20 or so wheelbarrow loads of small stones that were cleaned up on the property.

First, I gathered the unwanted rocks into piles. Then, in late summer, when the brook was barely flowing, one of my helpers wheeled them down to the stream and dumped them in two long piles spanning the streambed. Both piles were about three feet wide, enough to support a path one could walk across easily. Because the brook is small, I didn’t need pipes underneath the rocks. I simply made small channels for the water to run through.

Then my helper covered the rocks with several wheelbarrow loads of fill. I raked and washed the dirt between the rocks (conveniently using water from the stream); eventually it filled most of the spaces in the piles, where it helps stabilize the mass.

![]()

We added more fill to the top of the lower causeway, and I raked and tamped it down to make a hard, smooth walkway. Next I spread a thin layer of loam on the surface to make it look more natural.

We also added a layer of loam on the downstream side of the causeway and planted it with pachysandra; the ground cover soon grew thick and lush in the moist soil.

The lower causeway actually does triple duty:

- It takes you across the brook.

- It provides mid-stream views of cascades.

- When the stream contains at least a modest amount of water (in the spring or early summer or after a few days of heavy rain), it also dams the brook into a lovely pool—about 15 feet wide and 20 feet long and ringed by striking large, handsome, moss-covered boulders. In other words, the causeway not only creates the pool; it also provides the perfect place to view it, as well as the long chain of cascades falling into it.

![]()

Unlike the lower causeway, which crosses a long, nearly level section of the brook, the upper causeway spans a steep section, where sometimes-surging water washes away any fill or loam added to its surface. That’s one reason the upper causeway is more like a low stone footway than a typical causeway, and its stones need occasional refitting to keep them stable.

However, the upper causeway is a great viewpoint, too: It’s only inches from falling water both upstream and downstream, and it provides a long, aerial vista of more than 40 feet of cascades as they rush down to the pool above the lower causeway.

![]()

Most of the brook’s cascades are natural: Their size, shape, and location were determined, not by me, but simply by the size, shape, and location of the dozens of rocks occurring naturally in the streambed.

One waterfall, however, is completely artificial. I made it in the upper brook, near where the path curves sharply away from the stream and begins its descent of the West Bank. Here the brook flows over a low, rough, natural dam formed by a half-dozen large rocks. I dropped a sandbag in a gap in the dam through which most of the water flowed, and I concealed it with a big stone. Happily, this forced all the water in the brook to flow across a smooth, flat, nearly level rock, about three feet by two, which is naturally cantilevered over the edge of the stone dam. Now, when the stream is running, it fans fetchingly over the wide rock and trickles over its edge in a two-foot-wide, one-foot-high curtain of white water. It’s the most beautiful waterfall in the garden.

![]()

Planting

When all the work described above was finished—when all the subtraction was complete and all the berms, paths, ramps, and causeways were built—Evergreen had been transformed from what Shakespeare’s Hamlet called an “unweeded garden” into a clean, open, parklike woodland. And it was done without adding a single plant; that is, entirely without one instance of the very activity most commonly associated with gardening.

But while subtraction, grading and water features did wonderful work all by themselves, they still left Evergreen looking a bit . . . bare: rather like an empty room, or like a house after its inhabitants and their furniture have moved out. Just as even a beautiful, well-made house—like the one built by Dr. Backus at Evergreen—needs to be furnished, so even a well-groomed woodland garden needs the appointments of plants.

Woodland gardens created from existing woodlands usually don’t need more trees. Evergreen was already well furnished with the largest, most expensive plants that grow in any garden, and which were unavailable at any nursery at any price. It also had a small collection of ferns and other low-growing native plants.

![]()

Like many other woodland gardens, the plants Evergreen needed most were not trees or ground covers but shrubs. Shrubs occupy what designers call the middle layer of the garden, the layer closest to eye level, and, like many woodlands, Evergreen had virtually none.

I planted rhododendrons and other broadleaf evergreen shrubs for many reasons:

- Unlike deciduous plants, which are bare from fall to spring, broadleaf evergreen shrubs (like all evergreen plants) retain their foliage year round. That means we get to enjoy their leaves all the time, not only during the warmer months.

- Evergreen foliage provides a year-round canopy that suppresses weeds better than deciduous plants do, simply because the latter lose their leaves in cold weather.

- Evergreen foliage provides year-round screening of development around the garden.

- Unlike most needle evergreen shrubs (pines, spruces, etc.), which need sunlight, many broadleaf evergreen shrubs will tolerate shade.

- Broadleaf evergreen shrubs are also much showier than most needle evergreen shrubs because they produce colorful flowers. (Needle evergreen blossoms are practically invisible.)

I emphasized rhododendrons and mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) at Evergreen because their flowers are more—sometimes much more—colorful than the blossoms of other broadleaf evergreens.

And I emphasized rhododendrons most of all because they seem to blossom better than mountain laurel in shade (and, for that matter, better than virtually any other cold-hardy broadleaf evergreen shrub).

Many of the rhododendrons were planted on berms—for many reasons:

- Berms look rather bare without plants, but wonderful when blanketed with sweeps of shrubs.

- Berms, in fact, are ideal platforms for shrubs, because (like the audience in an amphitheater) plants on slopes are less apt to be hidden by plants in front of (and below) them. A group of plants on a berm will be more striking than the same plants on a flat surface because, on a berm, more of each plant (except plants in the front) will be visible, so the total visible plant mass will be greater.

- Rhodies on top of a berm provide higher screening than a berm by itself.

- Berms raise the rhodies higher up the “walls” of garden “rooms,” so the shrubs themselves seem taller, and the entire planting is more impressive.

- Planting berms is relatively easy, because the topsoil is fresher and softer than most garden soil, and there are no roots or large rocks in the way of a shovel blade.

![]()

I planted mainly two types of rhododendrons at Evergreen: rosebays (Rhododendron maximum) and Catawbas (Rhododendron catawbiense).

Both are large-leaved, shade-tolerant species native to the Appalachian Mountains of the southeastern United States, and both are hardy to temperatures as low as minus-30 degrees Fahrenheit.

Catawba rhodies tend to produce larger and more profuse flower trusses than rosebays do—though not in the heavy or even medium shade common to woodlands. Rosebays, on the other hand, will flower (albeit modestly) even in very dim light.

I planted a total of 175 rosebays in the darkest parts of the garden, most of them on berms. They’re especially valuable because they tend to grow tall—as much as 12 feet high in the Northeast (higher in the southern Appalachians)—so they can add substantial screening on top of a berm.

I planted a total of 220 Catawba rhodies, mainly in the less shady parts of the garden, such as on the large berms near Summer Street. I chose mainly “ironclad” varieties, so called because they’re among the toughest, hardiest cultivars. These included large sweeps of ‘Roseum Elegans,’ which produce dark pink flowers; and smaller groupings of ‘English Roseum,’ which have lighter pink trusses; ‘Nova Zembla,’ which sport red blossoms; and ‘Album,’ which is named for its white flowers. I also added ‘Hong Kong’ rhodies, which have yellow flowers, to the Gold Room.

Evergreen is most colorful when the Catawbas are at peak bloom—usually in very late May or very early June. That’s why Evergreen’s annual opening is always on the first weekend in June.

Nearly all these rhododendrons were planted before Evergreen’s first public opening in 1994; others were added after the fire of 2015, both events are described below.

![]()

Like many other broadleaf evergreen shrubs, mountain laurel flowers best in light (not heavy or medium) shade, so I planted it in the sunnier parts of the garden—on the West Bank of the brook, for example, and, after the fire of 2015, near the Garden Cottage.

Besides the species (Kalmia latifolia), which produces exquisite white blossoms, I also planted several cultivars with pink or red flowers.

I also added a few other, less colorful broadleaf evergreen shrubs for variety and accent. These include Japanese andromeda (Pieris japonica); Brower’s beauty andromeda, a cross between Japanese andromeda and mountain andromeda (Pieris floribunda); a couple of hollies (Ilex meserveae); and several varieties of leucothoe (Leucothoe fontanesiana). All are described in the Detailed Garden Description.

Other shrubs were used not for their flowers but for the colorful variegation of their new leaves. These included two leucothoe cultivars: ‘Girard’s Rainbow,’ named for its “rainbow” of red, white, yellow, and/or pink foliage tints; and ‘Silver Run,’ named for its prominent white streaks. ‘Girard’s Rainbow’ was planted at the edge of the Mirador, ‘Silver Run’ on the large slope nearby.

![]()

While shrubs furnish the middle layer of the garden, ground covers carpet its floors.

Probably Evergreen’s most valuable ground covers are variegated cultivars of Euonymus fortunei. Because they’re also evergreen and shade-tolerant, they’re among only a handful of plants that can provide foliage color all year long, even in deep shade. The large white splotches in the leaves of ‘Emerald Gaiety’ euonymus give them a creamy cast. The yellow in ‘Emerald ’n Gold’ foliage makes it look golden. And because euonymus is a vine, it spreads out along the ground and up the trunks of trees, bringing its color along the floor and up the walls of outdoor rooms.

Unfortunately, like virtually all variegated plants, its leaf colors are only white or yellow (and green). The plant breeder who somehow manages to create a red or pink euonymus will earn himself a seat at the right hand of God.

Euonymus does have one drawback: Deer love it. And when deer occasionally sneak into the garden in the middle of the night, euonymus seems to be their favorite food. But I like it at least as much as the deer do, so I planted it anyway and I continue to hope for the best. Luckily, euonymus growing along the ground is often covered by snow in the winter, so deer can’t get to it. And euonymus on trees often grows so high above the ground that deer can’t reach it.

![]()

Another valuable woodland garden ground cover is vinca (Vinca minor), also known as periwinkle, myrtle, or creeping myrtle. It’s vigorous, hardy, and easy-to-grow, and it creates thick, weed-suppressing mats of glossy evergreen foliage. More important, it’s one of a very few shade-tolerant evergreen ground covers to produce showy flowers; its namesake periwinkle blue blossoms appear in mid-spring (though, alas, the heavier the shade, the fewer the flowers). I planted vinca in the sunnier sections of Evergreen.

Several variegated cultivars create green-and-white or green-and-yellow-foliage; ‘Illumination’ is one of the best because its large yellow splotches can make its foliage look golden; I planted a large sweep of it around the planter in the Gold Room, as well as smaller patches elsewhere in the garden.

Unlike vinca, the flowers of pachysandra (Pachysandra terminalis) are rare and modest white pompoms. Pachysandra is valuable, however, because it too is a tough, vigorous plant, it thrives even in deep woodland shade, and its thick canopy of large, horizontal evergreen leaves shades out weeds. I used it throughout the shadier parts of Evergreen.

Its variegated cultivar ‘Silver Edge’ can bring white leaf color into the darkest parts of the garden. I planted large sweeps beside the path on the East Bank and West Bank of the brook.

![]()

I avoid most annual and perennial flowers because they’re high-maintenance plants. Unlike most trees and shrubs, they need frequent watering, and they either perish or die back to the ground in cold weather. Annuals of course also need annual planting. Unlike evergreen or woody species, annuals and perennials are part-time plants: The ground in which they grow is bare from fall to spring.

But I do make an occasional exception for hostas. They’re not evergreen; but they are shade tolerant; they sport large, elegant leaves, which give them uncommon presence; and the foliage of their blue, white-variegated, or yellow-variegated cultivars brings welcome color onto the floor of a woodland garden from mid-spring to fall. (The flowers are virtual afterthoughts.)

White-variegated cultivars such as Hosta undulata ‘Albomarginata’ are indispensable accents in the White Room, while yellow cultivars such as ‘Gold Standard’ or ‘Paul’s Glory’ fill the planter in the Gold Room, and ‘Fanfare’ is a focal point in the Northeast Niche. (All are described in the Detailed Garden Description.)

Unfortunately, hostas have two drawbacks:

- Slugs and snails love to eat them, and they can leave large, ugly holes in the foliage—that’s before they eat the entire plant to the ground. As a prophylactic measure, I scatter a chemical pesticide around the plants as soon as they emerge, and I replenish it throughout the summer.

- Also, like most perennials, hostas need regular watering. Without it, they can wither and die, even in shade. The garden once supported a vast sweep of white-variegated cultivars, which made a stunning composition. But, like the rest of Evergreen, it was watered only with snow melt and rain, and gradually the hostas perished. I replaced them with vinca and leucothoe ‘Silver Run,’ which, like other plants in the garden, can survive with only natural precipitation.

Some of the other hostas in the garden also show signs of stress. I may have to give those in the White Room, the Gold Room, and the Northeast Niche extra water; and I may replace other hostas with less demanding plants. See How Evergreen Is Maintained.

While hostas with colorful foliage may be a woodland garden’s most valuable perennials, impatiens may be its most desirable annual. That’s not only because impatiens are one of a small number of shade-tolerant annuals. They’re also one of the few annuals that will flower profusely in even heavy shade.

Because the Visitor Reception & Exhibit Area receives a lot of foot traffic, I paved it with crushed stone. To give the stone a bit of color, I set out seven handsome classical concrete urns, and each year Eileen and I plant them with fuchsia-colored impatiens. To reduce the need for watering, we amend the soil with a lot of peat moss, which retains a lot of moisture.

Soon after planting, the impatiens produce large, exuberant crowns of showy deep red blossoms.

![]()

You will probably not be surprised to hear that the soil in a woodland—especially a woodland of mature trees—is thick with tree roots (and usually at least a few stones). The roots especially make digging slow and difficult.

That’s why I always add a layer of topsoil before I plant. I add enough loam to cover the root balls of whatever I’m planting—about 9 to 12 inches for most shrubs, about 3 to 4 inches for most ground covers. This fresh, rootless, stoneless topsoil—rather like the soil in a berm—not only makes digging much easier. It also does two other wonderful things:

- It gives each plant its own private plot of ground. With its own soil, its roots don’t have to compete with the roots of long-established trees for food and water, because its roots are above their roots. The new plant will have exclusive use of all the resources in the soil around it, so it’s optimally sited for its fastest growth.

- The added soil automatically makes the new plant “larger.” A two-foot-high shrub planted in one foot of new soil, for example, becomes, in effect, a three-foot-tall shrub. Put another way, a $30 shrub becomes a $45 shrub, thanks to nothing more than extra topsoil.

![]()

Furniture and Sculpture

Evergreen is a low-maintenance garden mainly because it creates its beauty and interest with low-maintenance trees, shrubs, and ground covers. But even these low-care plants require a bit of gardening by subtraction (described above and in How Evergreen is Maintained).

Evergreen also creates beauty and interest with sculptures, which are often both powerful and colorful focal points. But unlike even low-care plants, sculptures require absolutely no cleaning up, no weeding, no pruning—and certainly no planting or watering. You simply set them up . . . and leave them alone. If there is such a thing as no-maintenance gardening, sculptures are it.

Among the most suitable figures for woodland gardens are realistic (not cute) portrayals of woodland animals in bronze, copper, cast iron, resin compound, or finely finished concrete. The most fitting animals are those that actually live in the garden or occasionally pass through it. Evergreen’s realistically posed deer and lop-eared rabbits are good examples. So are the turtles and frogs beside the brook.

While elaborate classical statuary is out of place in a naturalistic garden, simpler, less formal figures can work. The white cherub in the White Room, shading his eyes as he looks over the space, perfectly complements the plants—and automatically brings color and a strong focal point to the room. The sitting Buddhas are a strong calming presence.

It’s no coincidence that every one of these statues is placed by itself. For the effect of each one is most powerful when it competes with no other focal point; that is, when your attention is focused on the statute and nothing else. (If there were two (or three or more) statutes in the same place, your attention would be divided among competing focal points, because the focal power of each one would be vitiated by the focal power of the others.) Hence the designer’s rule of thumb: one space one focal point.

![]()

Evergreen’s sculpture is not only its statues. The garden’s elaborate white Victorian-style cast iron benches, for example, are much more than places to sit (and not completely comfortable ones either!). Just like the white cherub in the White Room, they’re also sources of low-maintenance beauty and color in a garden where color is often scarce. In other words, they do double duty: They’re both utilitarian and decorative. As the 19th-century critic John Ruskin famously put it, they’re both useful and beautiful at the same time.

Similarly, the finely detailed concrete planters in the Gold Room and the Visitor Reception & Exhibit Area are more than vessels for plants. They’re also beautiful pieces of sculpture.

![]()

Evergreen’s low-maintenance sculpture is not only its man-made statues. It’s also its natural legacy. As noted above, it includes its impressive, well-shaped granite boulders and the deeply furrowed bark and wide-flaring roots of its giant white pines.

![]()

First Public Opening, 1994

By 1994, after working on Evergreen for about eight years, most of the landscaping described above was completed, and I thought the garden was ready for its first public opening.

I planned the route of a garden tour and wrote a short guide, which was keyed to numbered stakes along the paths.

We decided to open the garden on the first weekend in June because that’s when its Catawba rhododendrons are at, or very close to, peak bloom.

Since then, Evergreen has been open to the public, without charge, every year on the first weekend in June (with one exception: See The Fire of 2015, below).

![]()

In 2005 Eileen and I moved to Montgomery Center, Vermont, where I later began work on a second woodland garden, a seven-acre tract I named the Birchwood. Because we wanted to preserve Evergreen and to ensure that it would continue to be opened to the public every year, we decided to rent the property instead of selling it.

![]()

Evergreen in the Open Days Program, 2010-2017

In 2010, Evergreen participated, for the first time, in the Open Days program of the Garden Conservancy, the national non-profit organization that opens exceptional private gardens to the public every year. The Conservancy also helps preserve America’s outstanding gardens, usually as non-profit organizations, so they can be regularly opened to the public; one of its first projects was the Fells estate on Lake Sunapee, in Newbury, New Hampshire. (More information about the Conservancy is available on its website, gardenconservancy.org.)

Evergreen was one of 11 private gardens on the Conservancy’s Monadnock Region/Greater Manchester Open Days on Saturday and Sunday, June 26 and 27. One of the gardens was one of my other projects: Water’s Edge, a two-acre property named for its location on a three-acre pond in Bedford, New Hampshire.

Since that weekend, Evergreen was a Merrimack Valley Open Days garden every summer until the fire of 2015 forced us to cancel participation both in that year and in 2016.

![]()

In 2013 Evergreen celebrated its 20th annual public opening with a free lecture at 11 a. m. on each of its three open days.

- On Friday, May 31, I explained how to transform wooded land into a woodland garden.

- On Saturday, June 1, I explained how to make low-maintenance gardens with trees, shrubs, and ground covers instead of high-care lawns and flower beds.

- On Sunday, June 2, I described how to create estatelike privacy with berms and other barriers.

![]()

In 2014, Evergreen was part of a unique Open Days event: Two of the seven gardens in the Garden Conservancy’s Merrimack Valley program were created (entirely coincidentally) by Evergreen’s next-door neighbors.

One of these extraordinary landscapes—directly across the street—was the work of Terri and Bob McKinnon. They transformed their entire three-quarter-acre lot into a vast collection of (mainly) perennial flowers, plus shrubs, ground covers, and vines. Now there’s no lawn for Bob to mow! The McKinnons also made their garden bigger by building terraces on their south slope. A retired mason, Bob supported the terraces with large, handsome, curving fieldstone retaining walls.

Sue and Denny Hooper, who live just south of Evergreen, transformed their front lawn into an exuberant, English-cottage-style collection of perennials supplemented by shrubs. Their back yard, which adjoins Evergreen, enjoys a similar landscape of mature white pines, ferns, and granite boulders; here the Hoopers created their own beautiful woodland garden, which they named Fernwood. Denny Hooper is also a co-founder and an original director of the Evergreen Foundation (see below).

The same Open Days program also included a garden I created for Jean Nelson on North Elm Street in Manchester. The Nelson Garden is an attempt to solve one of the most intractable problems of residential design: how to create, on a small, urban lot, the same privacy, intimacy, and visual integrity usually found only on much larger rural or suburban properties.

The solution was a U-shaped berm along the property boundary and sweeps of low-maintenance flowering evergreen shrubs on top of it. The berm-plus-plants screens out most of the neighboring houses and creates blossom color automatically from April through August.

![]()

The Fire of 2015

On June 22, 2015—barely two weeks after its annual public opening—a fire of unknown origin severely damaged the house at Evergreen. No one was at home at the time, and, fortunately, no one was injured; but we had to cancel Evergreen’s participation in the Merrimack Valley Open Days program the following month. Reconstruction also forced us to cancel Evergreen’s annual opening in June, 2016, as well as its Open Days event in July, 2016.

We demolished the main house, which sustained the greatest fire damage, early in the spring of 2016.

Then, during the summer and fall of 2016, we transformed the west wing of the structure into a two-story Garden Cottage with (1) a bathroom/service room for garden visitors, volunteers, and staff; (2) a basement to store garden tools and supplies; and (3) a two-bedroom rental apartment. The apartment ensures that Evergreen will continue to be a residential property, and the presence of a tenant will help deter vandalism and other mischief when the garden is not open and otherwise unoccupied.

In 2017, the site of the main house became the Visitor Reception & Exhibit Area, with a large, open, eight-sided pavilion to provide shelter. We added lattice to the nearly windowless east wall of the new Garden Cottage (which borders the Reception & Exhibit Area) and planted it with climbing hydrangea vine (Hydrangea anomala petiolaris). We planted most of the rest of the space with sweeps of rhododendrons.

We also filled in most of the inner driveway (which is edged with fieldstone walls) with gravel. We covered the gravel with loam and planted it with still more sweeps of flowering shrubs, mainly Catawba rhododendrons, but also P. J. M. rhododendrons, mountain laurel, and P. G. hydrangeas.

The 130 new shrubs made Evergreen even more of a garden, not only because they increased the number of its shrubs by more than 20 percent, but also because they replaced much of its architecture and about half of its asphalt with plants.

The new shrubs also extended Evergreen’s blooming season, which now runs from mid-spring (when the P. J. M. rhododendrons flower) to late summer (when the P. G. hydrangeas blossom).

All this new landscaping is described in the Detailed Garden Description.

![]()

Evergreen Foundation Formed, 2016

In May, 2016, Eileen and I joined Claire Baker, Denny Hooper, and Bob Lux to form the Evergreen Foundation, a New Hampshire charitable foundation, to “own, maintain, and preserve” Evergreen for the benefit of the public; and to undertake public education in horticulture and landscape design through the garden, lectures, and the Landscape Lyceum, the Foundation’s on-line landscape education forum.

In June, 2017, the Internal Revenue Service recognized Evergreen as a tax-exempt foundation under Section 501 (c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code. All donations to the Foundation are now federally tax deductible. See Friends of Evergreen.

In July, 2017, Eileen and I deeded Evergreen to the Foundation, which will continue to open the garden to the public without charge every year.

Because Evergreen is no longer a private residential garden, it will no longer be on the Garden Conservancy’s Open Days program. However, the Evergreen Foundation plans to open Evergreen to the public whenever the Conservancy sponsors Open Days in New Hampshire.

![]()

Evergreen reopened to the public for the first time since the fire of 2015 on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, June 2, 3, and 4, 2017.

![]()

Evergreen celebrated its 25th annual public opening on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, May 31 and June 1 and 2, 2019.

![]()

Evergreen did not open during the COVID pandemic, but reopened in 2022.